Doris Leuenberger / Patrick Herzig

INTRODUCTION

The Swiss League for Human Rights (LSDH) is an association under articles 60 et seq. of the Swiss civil code. It is a member of the International Federation of Human Rights Leagues (Fédération internationale des ligues des droits de l’homme, FIDH).

The Swiss League under the name of Ligue suisse des droits de l’homme et du citoyen (Swiss League for Human and Citizen Rights) was founded in 1928, but according to Suzanne Colette-Kahn, former Secretary General of the International Federation, Switzerland was already represented at the first convention of the International League taking place in Paris on 28 May 1922.(1) It seems reasonable to assume that some preparatory work occurred before the foundation in 1928, but no evidence of such preparations has been found as yet. Further research might shed some light on this matter.

ABOUT THE ARCHIVES OF THE SWISS LEAGUE

At this point in our research, we have not been able to find any previous academic work about the history of the Swiss League. Following the information available to us at the time of writing, archive material could be found in the National Archives in Bern, at the Geneva Library, and in the League’s own archives. The latter consist of documents transferred to the League after the death of M. Robert Emery, former president of the Geneva section, as well as other documents of hitherto unknown sources. This body of archives has not yet undergone proper filing due to the resource requirements involved, but it is certainly a project that the League will attempt to pursue in the future.

The documents found at the Geneva Library were rapidly examined, but revealed very little regarding the period between the League’s foundation in 1928 and the election of M. Henri Bartholdi as president in 1933. Nothing has been found so far about any preliminary work prior to 1928. After M. Bartholdi’s election, the existing documents mainly pertain to the years 1933–1939 and the period starting in 1947. The body of files is comprised of letters regarding individual cases that the League became involved in, various articles published in the press, and several letters written to authorities in Switzerland and abroad on subjects of general interest.(2) The sorting and recording of this material likewise represents an important endeavour for the future.

Lastly, the documents found in the National Archives partly refer to Henri Bartholdi and other members of the League or people close to the cause. Other documents concern the League itself but have not yet been examined due to the limited time and resources at our disposition. The materials we have been able to examine, albeit merely superficially so far, consist mainly of police and secret service reports about the activities of some of the League’s members and supporters. Once confidential, these documents were declassified following the “secret files scandal” of the 1980s. They reveal that certain League members were considered to be of interest to national security because of their activities as antimilitarists or anarchists.(3)

For the period starting after World War II, the amount of available material is greater and following the activity of the Swiss League becomes easier, although details remain somewhat scarce.

Throughout the years, various bulletins were published by different sections of the Swiss League.(4) There was not a single continuous publication, however, but rather a series of attempts made by the Swiss League as a whole and by some of its sections. It is important to note that the rather loose organisation of the League and the persistent difficulty of securing long-term involvement in its activities created a situation where sections would emerge in places where people decided to act on behalf of human rights and last only as long as those people could maintain the activity themselves. Many of these initiatives were short-lived and apparently did not leave behind much documentation. It is possible, however, that further research will bring new sources to light.

MAIN ACTIONS OF THE SWISS LEAGUE SINCE ITS CREATION IN 1928

According to the archives at our disposition concerning the years preceding the Second World War, the Swiss League was mainly concerned with providing help and counsel to people seeking authorisation to take up residence in Switzerland as well as helping refugees from all countries flee the insecurity and repression imposed on them by the general rise of totalitarianism in Europe and find countries of asylum, as Switzerland was rarely ready to do so. On the national front, the League also participated in the debates and actions which would eventually lead to the introduction of retirement and unemployment laws in Switzerland.

From the early 1930s onward, the League concerned itself with the situation of Jews and other people threatened by the rise of totalitarianism in Italy, Spain and Germany. In 1933, it organized a public gathering in Geneva of more than six hundred people during which a resolution against Hitler and the German regime was adopted and publicised.(5)

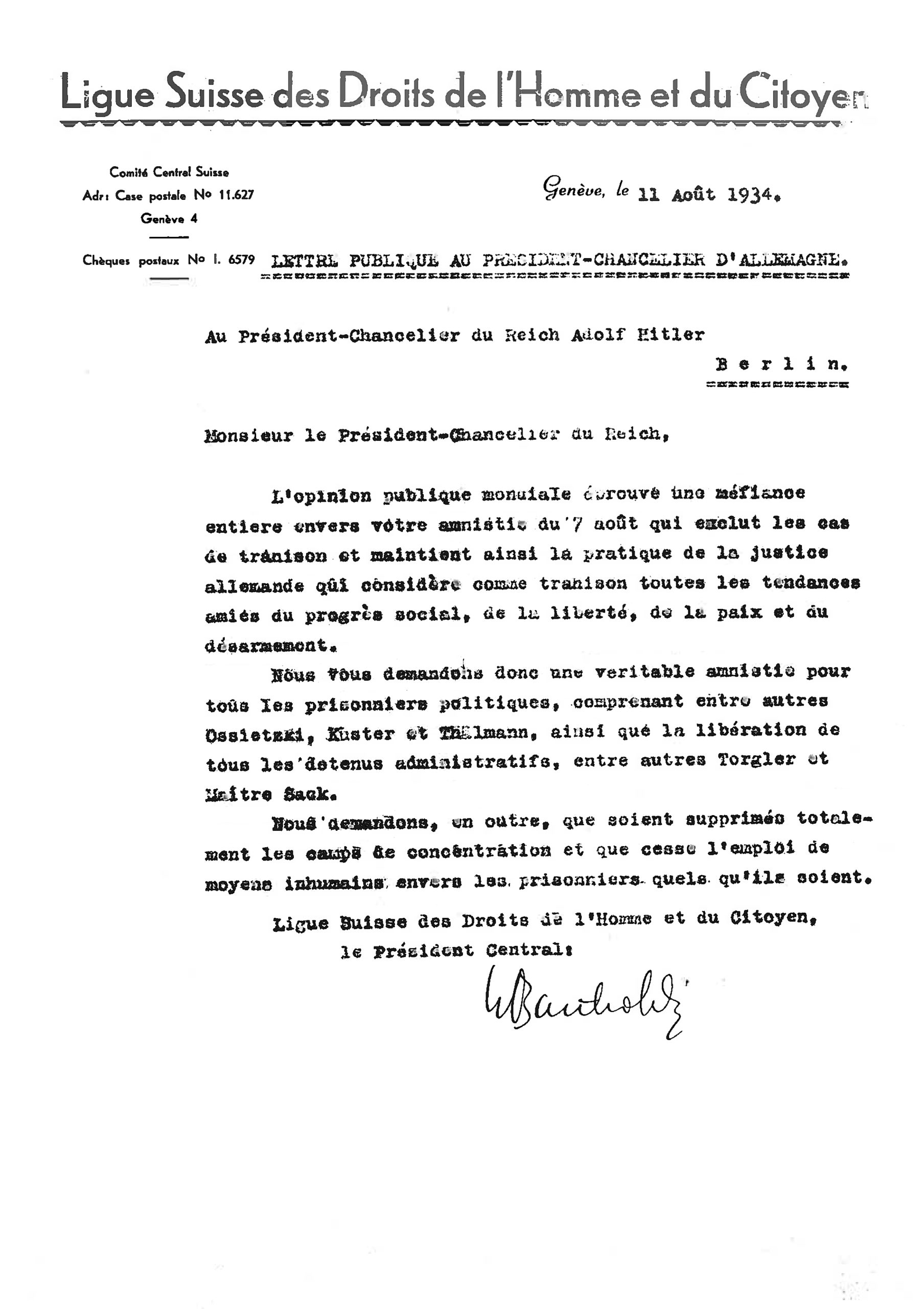

It was in this context that Henri Bartholdi, then president of the League, wrote an official letter to the President and Chancellor of the Reich, Adolf Hitler, on 11 August 1934 in which the League, with reference to the international mistrust towards the so-called amnesty declared by Hitler on 7 August 1934 (6), unequivocally asked for this amnesty to be fully implemented, notably by liberating all political prisoners. The letter also called for the immediate closing of all concentration camps and the termination of all inhuman treatment of prisoners regardless of the reasons for their imprisonment. A translation of this letter follows, with the French original reproduced in Figure 1, overleaf.

Geneva, 11 August 1934

OPEN LETTER TO THE PRESIDENT-CHANCELLOR OF GERMANY

To Reich President-Chancellor Adolf Hitler, Berlin

Mister Reich President-Chancellor,

global public opinion absolutely distrusts your amnesty of August 7th, which excludes cases of treason and thus upholds the German justice’s practice of considering as treason all tendencies friendly to social progress, freedom, peace and disarmament.

We therefore demand a true amnesty for all political prisoners, including, among others, Ossietzky, Küster and Thälmann, as well as the liberation of all administrative detainees, Torgler and Dr. Sack amongst others.

We also demand all concentration camps to be abolished altogether, and all inhuman treatment of prisoners to cease, whoever they are.

The Swiss League for Human and Citizen Rights, The Central President

H. Bartholdi

It is interesting to note that direct reference is made in this letter to concentration camps and inhuman treatments, while knowledge of the existence of such camps and treatments was later downplayed or denied by parts of the international community (7) and the Swiss government (8). During the war, the League fought against the asylum policy of the Swiss government which, following the slogan “The boat is full”, allowed thousands of Jews to be sent back to Germany and die in concentration camps (9).

After 1945, the League resumed its efforts begun before the war in favour of the adoption of a retirement law which, after having been rejected in 1931, was finally voted for by the people in 1947 and introduced on 1 January 1948.

The struggle for the unemployment law took longer, with the League active until the final outcome in 1982, when compulsory membership of all employees in the unemployment insurance system was introduced (10).

Another important subject which occupied the League on a long-term basis was the question of political equality for women and men. While the first parliamentary action dated back to 1919, it was not before 1929 that a first petition was presented to the government. Despite having collected 249,237 signatures, the petition was ignored. The crisis of the 1930s and World War II put a temporary stop to the movement, which was later reactivated through a series of actions during the 1950s. The 1960s brought fresh impulses to the debate, and Swiss women finally achieved full suffrage in 1971 – although on the cantonal level, the struggle continued until 1991 (11).

The League was also involved in the lengthy and unfinished business of the introduction of a civilian service as an alternative to the compulsory military service still in force in Switzerland today. Much of the influence resulting in the establishment of a civilian service accepted by public vote in 1992 and introduced in 1996 came by way of revendication of the right to conscientious objection advocated since the 1900s, which the League supported and fought for with determination.

Another struggle undertaken by the Swiss League was that for the abolition of the status of seasonal workers applied to foreigners immigrating to Switzerland to find work since 1934. After a protracted process and much debate and conflict, this discriminatory status was finally abolished in 2002 when the free circulation agreement between Switzerland and the European Union came into effect (12). Unfortunately, as is the case with the compulsory military service, the story of this policy change is far from over. As a result of the current migrant crisis and the fact that right-wing ideas on the subject currently seem to represent the majority opinion in the country, the possibility of reintroducing the status of seasonal workers has been expressed and there is a real risk that this struggle may have to be fought again (13).

In addition, the League was and still is actively engaged in opposing the national and cantonal policies of administrative and psychiatric internment, notably in relation to the asylum policy to which the League likewise still objects to this day.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the Swiss League participated actively in many campaigns against the remaining dictatorships in Europe: the regime of General Franco in Spain, the dictatorship of the colonels in Greece, and the discriminatory measures applied to political refugees from the Eastern Bloc, like Hungarians. It was also active in the defence of political refugees from South America (Argentina, Chile, Brazil and Bolivia), and concerned with helping the victims of oppression in South Africa, Afghanistan, Cambodia, Equatorial Guinea, Iran, Poland, Morocco and Czechoslovakia. In addition, the League supported the Armenian people, Gypsies, Indians, Kurds, Palestinians and the Sahraoui people in their struggles to obtain equal rights, fair treatment, freedom and the right to independence. During this period, the League was also active in the international movement to stop the Vietnam War.

In Switzerland in 1989–1990, the League joined the outcry following the uncovering of what has become known as the “secret files scandal”, a secret system of spying and collecting data on supposedly leftist Swiss citizens suspected of communist political activities by the authorities and subjected to unlawful scrutiny by the secret service agencies.

Throughout the years the Swiss League, through its sections, has been involved in defending human rights in relation to the conditions of both penal and administrative detention in Switzerland. One of the key activities consisted (and still consists) in visiting prisoners and taking steps to protect their rights as well as maintaining close contact with the authorities to promote respect for human rights in all aspects of penitential policy.

The Swiss League is also engaged in the promotion of the rights recognized by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights adopted by the United Nations on 16 December 1966 and put into force on 23 March 1976.

Last but not least, since the beginning of the 21st century the Swiss League has been involved in various international missions of observation related to political trials in Morocco (2007), Tunisia (2001–2002), Cameroon (2005), Western Sahara (2005–2008), and the Colonna case in France (2007) (14).

THE ORGANISATION OF THE SWISS LEAGUE.

AN OVERVIEW OF MAJOR EVENTS SINCE 1964

The Swiss League is organised in sections under a national bureau called the Central Committee. All sections have the right to be represented in this committee according to the number of members they represent. The committee holds an annual meeting during which the governing body is elected and votes are held on issues concerning the national policy of the League (15).

Between 1964 and 1995, the various sections of the Swiss League participated in 28 national conventions, and the Central Committee met 34 times. This activity shows a vivid interest in the situation of human rights in the country as well as in the actions undertaken by the League and its sections, both nationally and internationally.

The number of cantonal sections varied during this period: In 1964, following a meeting with Henri Bartholdi, author of the letter to Hitler in 1934, a “Militant Assembly” was organised in Bienne (canton of Bern) that was attended by militants from five cantons: Geneva, Vaud, St. Gallen, Basel and Chaux-de-Fonds (Neuchâtel). Henri Bartholdi was elected president of the Swiss League, and Geneva was chosen as the association’s seat. The seat later moved to Basel in 1967 before returning to Geneva in 1968.

In the following years, national conventions were organised on an irregular basis with varying attendance by sections from cantons or sometimes even cities (Bienne, Chaux-de-Fonds, Winterthur). As mentioned above, these conventions were generally represented occasions to organise public conferences and debates on important topics of the time. Such topics included the issue of torture in Brazil and the Vietnam war in 1970, the relations between Israel and Iraq and the situation resulting from the counterproductive involvement of one member of the Swiss League in the RAF/Schleyer affair in 1977, or the situation of refugees in 1984. Later that same year, an extraordinary convention was organised to discuss the question of “data processing and liberties” in relation to the consulting procedure preceding the introduction of a new law on “the protection of personal data”; in 1986, the convention was followed by a demonstration against the conditions in Swiss prisons; in 1990, the topic was the “secret files scandal” mentioned above; in 1991, the creation of a fund for the victims of torture was discussed; and in 1995, a further debate was organised on the situation in Swiss prisons.

In 1989, the Swiss League participated in an event organized by the FIDH in Paris focusing on the general state of human rights in the world.

Unfortunately, since 1995 many sections have dispersed and disappeared, with the notable exception of the Geneva section which, for the following years until 2008, bore the sole responsibility of maintaining the existence of the League for Human Rights in Switzerland.

In 2008, thanks to the initiative of two students from the Faculty of Political Science at the University of Lausanne, a section was re-established in the canton of Vaud, allowing for a new Central Committee to be formed and providing new energy to the action of the League.

CONCLUSION

Despite the fact that the Swiss League for Human Rights is a small organisation in comparison to some others, it has existed continually since its creation in 1928 and has had a significant influence on key human rights issues both in Switzerland and at the international level. It is fair to say that its reputation as a financially independent, non-political and non-religious organisation has benefitted the actions taken by the League and granted an aura of respectability to the views expressed by it that has been favourable to the causes the League chose to defend. As the complexity of the world increases with the passage of time, the Swiss League’s mission to scrutinise and become involved in human rights issues will remain of importance, and it will continue to be pursued thanks to the personal commitment of its members.

NOTES

- Wolfgang Schmale / Christopher Treiblmayr, Human Rights Leagues and Civil Society (1898–ca. 1970s), in: Historische Mitteilungen 27/2015, 186–208, 204.

- Papiers Henri Bartholdi, Bibliothèque de Genève, Catalogue des manuscrits, ref.: CH BGE Non catalogué (1972/3).

- Schweizerisches Bundesarchiv, Bern, ref.: CH-BAR#E4320B#1978-121#72.

- Within the body of archives inspected so far, different prints of the same publication entitled “La Lettre” and dated between 1987 and 1995 were found. The letter was published primarily by the Vaud section and once by the Swiss Italian section. It is likely, however, that other bulletins were published by other sections.

- Papiers Henri Bartholdi, Annex to a letter in 1959 from H. Bartholdi to P. Lavastre, president of the French League, 3rd volume of documents, Papiers Henri Bartholdi, Bibliothèque de Genève, Catalogue des manuscrits, ref.: CH BGE Non catalogué (1972/3).

- Papiers Henri Bartholdi, 1st volume of documents, Papiers Henri Bartholdi, Bibliothèque de Genève, Catalogue des manuscrits, ref.: CH BGE Non catalogué (1972/3). N.B.: The mentioned amnesty freed thousands of common law criminals, but excluded communists and prisoners convicted of treason, violence and terrorism. See Jewish Telegraphic Agency, Hitler Amnesty Frees 10,000 Foes of Nazis, consulted 8 September 2016; see also Stanislav Zámečník, C’était ça, Dachau. 1933–1945, Paris 2003.

- On this subject, see among others Yannick Haenel, Jan Karski, Paris 2009.

- See also , Independent Commission of Experts Switzerland – Second World War, Switzerland, National Socialism and the Second World War. Final Report, 119, consulted 8 September 2016.

- See flyer of the Ligue suisse des droits de l’Homme, section vaudoise (date and year of publication unknown).

- Charlotte Pellaz / Véronique Pipoz / Thomas Lufkin, Révision de la loi sur l’assurance chômage, 8, consulted 8 September 2016.

- Confédération suisse, Pourquoi les femmes n’ont-elles eu le droit de vote et d’éligibilité qu’à partir de 1971? consulted 8 September 2016.

- Silvia Arlettaz, Saisonniers, in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse, consulted 8 September 2016.

- http://www.unia.ch/uploads/tx_news/Events_20141107-Saisonnierausstellung.pdf, consulted 8 September 2016.

- See the mission reports on the LSDH website, consulted 8 September 2016.

- Statuts de la Ligue suisse des droits de l’Homme, Archives of the Swiss League for Human Rights.